207x Filetype PDF File size 0.55 MB Source: lawreview.law.ucdavis.edu

Global Justice in Healthcare:

Developing Drugs for the Developing

*

World

** ***

William W. Fisher & Talha Syed

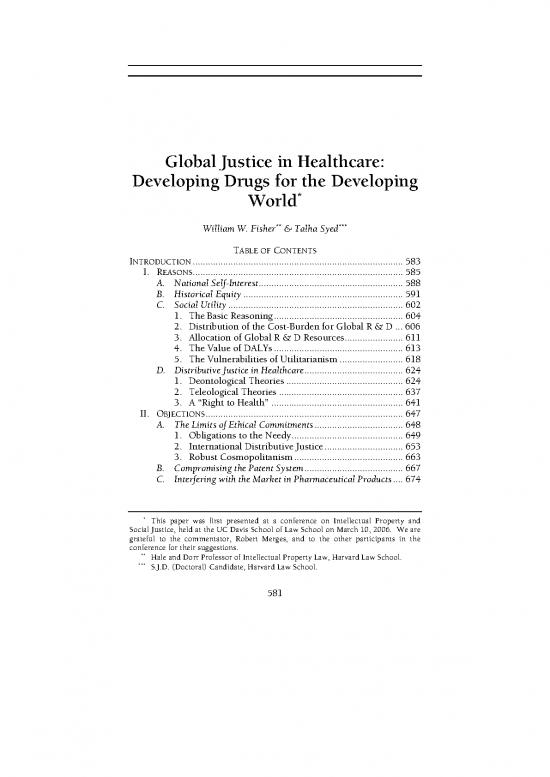

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION................................................................................... 583

I. REASONS................................................................................... 585

A. National Self-Interest......................................................... 588

B. Historical Equity............................................................... 591

C. Social Utility..................................................................... 602

1. The Basic Reasoning................................................... 604

2. Distribution of the Cost-Burden for Global R & D ... 606

3. Allocation of Global R & D Resources....................... 611

4. The Value of DALYs................................................... 613

5. The Vulnerabilities of Utilitarianism......................... 618

D. Distributive Justice in Healthcare....................................... 624

1. Deontological Theories.............................................. 624

2. Teleological Theories................................................. 637

3. A “Right to Health”.................................................... 641

II. OBJECTIONS.............................................................................. 647

A. The Limits of Ethical Commitments................................... 648

1. Obligations to the Needy............................................ 649

2. International Distributive Justice............................... 653

3. Robust Cosmopolitanism........................................... 663

B. Compromising the Patent System....................................... 667

C. Interfering with the Market in Pharmaceutical Products.... 674

* This paper was first presented at a conference on Intellectual Property and

Social Justice, held at the UC Davis School of Law School on March 10, 2006. We are

grateful to the commentator, Robert Merges, and to the other participants in the

conference for their suggestions.

**

Hale and Dorr Professor of Intellectual Property Law, Harvard Law School.

***

S.J.D. (Doctoral) Candidate, Harvard Law School.

581

582 University of California, Davis [Vol. 40:581

***

2007] Global Justice in Healthcare 583

INTRODUCTION

Each year, roughly nine million people in the developing world die

from infectious diseases.1 The large proportion of those deaths could

be prevented, either by making existing drugs available at low prices

in developing countries, or by augmenting the resources devoted to

the creation of new vaccines and treatments for the diseases in

question. Several legal and social circumstances contribute to this

outrage. In this Article, we focus on two. First, the majority of the

most effective drugs are covered by patents, and the patentees typically

pursue pricing strategies designed to maximize their profits. Second,

pharmaceutical firms concentrate their research and development (“R

& D”) resources on diseases prevalent in Europe, the United States,

and Japan — areas from which they receive 90-95% of their revenues

— and most of the diseases that afflict developing countries are

uncommon in those regions.

In a forthcoming book,2 we substantiate the foregoing assertions —

some of which are controversial — and then consider several ways in

which the legal system might be modified to overcome the two

obstacles and thus help alleviate the crisis. Some of the possible

reforms we examine involve providing pharmaceutical firms financial

incentives to modify their pricing practices or R & D policies; others

would use various legal levers to force the firms to modify their

behavior; still others would increase the roles of governments in the

development and distribution of pharmaceutical products. We then

attempt to identify a politically palatable package of reforms that

would both result in lower prices in developing countries for existing

drugs and accelerate the production of new drugs that address the

health crises in those areas.

Our analysis gives rise to an ethical problem: most of the legal

reforms we consider would increase the already significant extent to

which the cost of developing new drugs — including some whose

1 By comparison, the same diseases claim 200,000 lives in the developed world, a

region containing one quarter as many people. In other words, the mortality rate from

infectious diseases is over ten times higher in the developing world than in the

developed world. These figures are derived from WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION,

WORLD HEALTH REPORT: CHANGING HISTORY 2004 (2004), available at

http://www.who.int/whr/2004/en/. Throughout this Article we will adopt the World

Health Organization’s (“WHO”) usage and use the terms “developed” and

“developing” countries or worlds, which are roughly synonymous with “North” and

“South,” “First World” and “Third World,” and “the West” and “the Rest.” Each pair

of terms has its drawbacks.

2 WILLIAM W. FISHER & TALHA SYED, DRUGS, LAW, AND THE HEALTH CRISIS IN THE

DEVELOPING WORLD (forthcoming) (manuscript on file with authors).

584 University of California, Davis [Vol. 40:581

principal function is to alleviate suffering in the developing world —

is borne by the residents of the developed world, either as consumers

purchasing patent-protected drugs or as taxpayers. Why should the

law be organized in this fashion? The goal of this Article is to answer

that question.

The analysis proceeds in two stages. In Part I, we consider several

possible reasons why developed country residents should help

alleviate the health crisis in the developing world. We begin by

canvassing, briefly, considerations from national self-interest. Finding

these implausible and unattractive, we then consider several

arguments grounded in considerations of justice, or in sentiments of

mutual concern and well-wishing, that extend beyond national

borders. These include arguments from historical equity, social

utility, and deontological and teleological theories of distributive

justice. We show that each of these frameworks or perspectives

provides support for our proposals. Further, we contend that, not

only do the arguments individually support our goals, but, suitably

qualified, each tends to reinforce, or at least converge or “overlap”

3

with, the others.

In the course of our analysis in Part I, we address several criticisms

that have been or might be made of particular arguments we offer in

support of our proposals. In Part II, we confront the following more

sweeping objections to our approach: that full acceptance of the

commitments we identify would impose intolerable moral burdens on

the citizens of developed countries; that questions of distributive

justice are properly limited to the level of individual polities; that

3 We mean to invoke, loosely, the concept of “overlapping consensus” developed

by John Rawls in Political Liberalism. JOHN RAWLS, POLITICAL LIBERALISM 385-95

(expanded ed., Columbia Univ. Press 2005) (1993). Rawls offered the concept as a

solution to the problem of disagreements between “comprehensive doctrines” or

worldviews. Id. at 385-86. It seemed unlikely to him that reason could solve such

disagreements. Id. at 387. Consequently, as a “political” solution to this “fact of

reasonable pluralism” in the realm of moral metaphysics, he urged that, when

debating core issues of public life, efforts be made to find an “overlapping consensus”

about the fair terms of social cooperation. Id. at 390-91. This entails framing

arguments in a shared vocabulary of “public reason,” so that adherents to different

“reasonable” comprehensive doctrines can recognize the arguments of others as

congruent with, or even representing in altered form, their own deeper commitments.

Id. at 392. Without committing ourselves to the assumptions underpinning Rawls’s

overall enterprise, we point out that a rough parallel exists between his concept and

our attempt here to accommodate current disagreements (although in our case the

disagreements are not between worldviews but between rival political philosophies,

and they do not concern Rawls’s “constitutional essentials” so much as “legislative”

questions of social policy).

no reviews yet

Please Login to review.